Sandinista National Liberation Front

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2019) |

Sandinista National Liberation Front Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | FSLN |

| Secretary-General | Daniel Ortega |

| Founder |

|

| Founded | 19 July 1961 |

| Headquarters | Leal Villa De Santiago De Managua, Managua |

| Newspaper | La Voz del Sandinismo |

| Youth wing | Sandinista Youth |

| Women's wing | AMNLAE |

| Membership (1990) | <95,700[1][needs update] |

| Ideology |

|

| Political position | Left-wing[15][16] Historical: Far-left[17][18] |

| Religion | Christianity[a] |

| Regional affiliation | Parliamentary Left Group (Central American Parliament) |

| Continental affiliation | São Paulo Forum COPPPAL |

| Union affiliate | Sandinista Workers' Centre |

| Colors | Official: Red Black Customary: Carmine red |

| National Assembly | 75 / 90 |

| Central American Parliament | 15 / 20 |

| Flag | |

| |

The Sandinista National Liberation Front (Spanish: Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, FSLN) is a Christian socialist political party in Nicaragua. Its members are called Sandinistas (Spanish pronunciation: [sandiˈnistas]) in both English and Spanish. The party is named after Augusto César Sandino, who led the Nicaraguan resistance against the United States occupation of Nicaragua in the 1930s.[19]

The FSLN overthrew Anastasio Somoza Debayle in the 1979 Nicaraguan Revolution, ending the Somoza dynasty, and established a revolutionary government in its place.[20][21] Having seized power, the Sandinistas ruled Nicaragua from 1979 to 1990, first as part of a Junta of National Reconstruction. Following the resignation of centrist members from this Junta, the FSLN took exclusive power in March 1981. They instituted literacy programs, nationalization, land reform, and devoted significant resources to healthcare, but came under international criticism for human rights abuses, including mass execution and oppression of indigenous peoples.[22][23] They were also criticized for mismanaging the economy and overseeing runaway inflation.[24]

A US-backed group, known as the Contras, was formed in 1981 to overthrow the Sandinista government and was funded and trained by the Central Intelligence Agency.[25] The United States sought to place economic pressure on the Sandinista government by imposing a full trade embargo[26] and by planting underwater mines in Nicaragua's ports.[27] In 1984, free and fair elections were held,[28][29] but were boycotted by opposition parties. The FSLN won the majority of the votes,[30] and those who opposed the Sandinistas won approximately a third of the seats. The civil war between the Contras and the government continued until 1989. After revising the constitution in 1987, and after years of fighting the Contras, the FSLN lost the 1990 election to Violeta Barrios de Chamorro in an election marked by US interference,[31] but retained a plurality of seats in the legislature. The FSLN is now Nicaragua's sole leading party. In the 2006 Nicaraguan general election, former FSLN President Daniel Ortega was reelected President of Nicaragua with 38.7% of the vote to 29% for his leading rival, bringing in the country's second Sandinista government after 17 years of other parties winning elections. In October 2009, the Supreme Court, which has a majority of Sandinista judges, overturned presidential term limits that were set by the constitution. Ortega and the FSLN were reelected in the presidential elections of 2011, 2016, and 2021, although these elections have been criticized by international observers.[32][33][34]

History

[edit]Origin of the term Sandinista

[edit]The Sandinistas took their name from Augusto César Sandino (1895–1934), the leader of Nicaragua's nationalist rebellion against the US occupation of the country during the early 20th century (ca. 1922–1934). The suffix "-ista" is the Spanish equivalent of "-ist".

Sandino was assassinated in 1934 by the Nicaraguan National Guard (Guardia Nacional), the US-equipped police force of Anastasio Somoza, whose family ruled the country from 1936 until they were overthrown by the Sandinistas in 1979.[citation needed]

Precursor to Revolution (1933–1961)

[edit]The second U.S. intervention in Nicaragua ended when Juan Bautista Sacasa of the Liberal Party won the elections. By 1 January 1933 there wasn't a single US soldier left on Nicaraguan soil, however in 1930 the US had formed a group for national security known as the National Guard. The National Guard remained after the exit of the U.S. under the leadership of Anastasio Somoza Garcia who was supported by the U.S. On 21 February 1934, Somoza, using the National Guard, assassinated Sandino who opposed and fought against US intervention. This was the first act of a series that Somoza, with help from the U.S., would take that would culminate in his election as president in 1936. The result of his election was the start of the U.S. sponsored dictatorship of the Somoza family.[35]

During the 1960s, leftist ideas began spreading worldwide, sparking independence movements in different colonial territories. On 1 January 1959 in Havana, Cuban revolutionaries fought against dictator Fulgencio Batista. In Algeria the Algerian National Liberation Front was founded to fight against French colonial control. In Nicaragua, different movements that opposed the Somoza dynasty began to unite, forming the Nicaraguan National Liberation Front which would later be renamed the Sandinista National Liberation Front.

The economic situation of Nicaragua in the mid-20th century had deteriorated as the prices of agricultural exports such as cotton and coffee dropped. Politically, the conservative party of Nicaragua split and one of the factions, the Zancudos, began collaborating with the Somoza regime.

Anastasio Somoza Garcia was assassinated by poet Rigoberto Lopez Perez in 1956.

In 1957 Carlos Fonseca Amador, Silvio Mayorga, Tomás Borge, Oswaldo Madriz y Heriberto Carrillo formed the first cell of the Nicaraguan Revolutionary Committee who identified with the issues of the proletariat. Later that October, the Mexican cell was formed with members such as Edén Pastora Gómez, Juan José Ordóñez, Roger Hernández, Porfirio Molina y Pedro José Martínez Alvarado.

In October 1958 Ramon Raudales began his guerilla war against the Somoza dynasty beginning the armed conflict.

June 1959 the event known as "El Chaparral" occurred in Honduran territory bordering Nicaragua. The guerrilla fighters "Rigoberto López Pérez"[36] under the command of Rafael Somarriba (in which Carlos Fonseca was integrated) was found and annihilated by the Honduran Army in coordination with the intelligence services of the Nicaraguan National Guard.

After "El Chaparral", several more armed rebellions took place. In August the journalist Manuel Díaz y Sotelo died; in September Carlos "Chale" Haslam died; in December Heriberto Reyes (Colonel of the Defensive Army of National Sovereignty) died. The following year the events of "El Dorado" (February 28, 1960) took place where several events occurred[37] leading to several deaths including Luis Morales, Julio Alonso Leclair (head of the September 15 column), Manuel Baldizón and Erasmo Montoya.

The conventional opposition, up to that point led by the Nicaraguan Communist Party, had not been able to form a common front against the dictatorship. The opposition to the dictatorship was established around various student organizations. Among its leaders, Carlos Fonseca Amador in the early 1960s.

At the start of 1961 the New Nicaragua Movement (NNM) was founded by prominent leaders in education like Carlos Fonseca, Silvio Mayorga, Tomás Borge, Gordillo, Navarro y Francisco Buitrago; prominent leaders on workers issues such as Jose Benito Escobar; countryside leaders like Germán Pomares and small business leaders such as Julio Jerez Suárez. Legendary guerilla veteran Santos Lopez, who fought with Augusto Cesar Sandino, also participated in the NNM.

The New Nicaragua Movement was established in three cities Managua, Leon and Estelí, however they were generally stationed in Honduras. Their first public activity was held in March 1961, in support of the Cuban revolution and in protest of the position that the Nicaraguan government held with Cuba. The NNM later dissolved to make way for the National Liberation Front.

The New Nicaragua Movement soon dissolved with its members forming the National Liberation Front, FLN.

Founding (1961–1970)

[edit] |

|---|

|

|

The FSLN originated in the milieu of various oppositional organizations, youth and student groups in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The university of Léon, and the National Autonomous University of Nicaragua (UNAN) in Managua were two of the principal centers of activity.[38] Inspired by the Revolution and the FLN in Algeria, the FSLN was founded in 1961 by Carlos Fonseca, Silvio Mayorga, Tomás Borge, Casimiro Sotelo and others as The National Liberation Front (FLN).[39] Only Borge lived long enough to see the Sandinista victory in 1979.

A congress or assembly is not formed between all the prominent leaders of the various groups as the preparation would have required a prior theoretical process in order to create them. As a result, the FSLN was not prepared for its own formation. Different discussions took place within the group as they came to a consensus on political ideas. Even in 1963, while still under the name of FLN, there was a lack of internal coherence in political ideas (this can be seen in the publication of the newspaper Trinchera). The first few years were carried by some basic shared values of all the forces that were being integrated. Some of these basic shared ideas was to imitate the success of the Cuban Revolution, the ineffectiveness of the conventional opposition to the Somoza regime and the need to remain independent of them (referring to the from the conservative, liberal and communist parties), the need for a revolutionary movement that would use the armed struggle as opposition to the Somoza dictatorship, and after some discussion, identification with Sandino's struggle. It was not until 1969 that any programmatic document was published.

The Sandinista National Liberation Front was supposedly founded in a meeting in Tegucigalpa (Honduras) between Carlos Fonseca, Tomás Borge, and Silvio Mayorga. It's even been said that the meeting was held on July 19, 1961. In reality, there is no documentary reference that supports this affirmation, with the first news of this meeting and date surfacing after the revolutionary triumph of 1979.

The term "Sandinista" was adopted two years later, establishing continuity with Sandino's movement, and using his legacy to develop the newer movement's ideology and strategy.[40] By the early 1970s, the FSLN was launching limited military initiatives.[41]

Rise (1970–1976)

[edit]On December 23, 1972, a magnitude 6.2 earthquake leveled the capital city, Managua. The earthquake killed 10,000 of the city's 400,000 residents and left another 50,000 homeless.[42] About 80% of Managua's commercial buildings were destroyed.[43] President Anastasio Somoza Debayle's National Guard embezzled much of the international aid that flowed into the country to assist in reconstruction,[44][45] and several parts of downtown Managua were never rebuilt. The president gave reconstruction contracts preferentially to family and friends, thereby profiting from the quake and increasing his control of the city's economy. By some estimates, his personal wealth rose to US$400 million in 1974.[46]

In December 1974, a guerrilla group affiliated with FSLN directed by Eduardo Contreras and Germán Pomares seized government hostages at a party in the house of the Minister of Agriculture in the Managua suburb Los Robles, among them several leading Nicaraguan officials and Somoza relatives. The siege was carefully timed to take place after the departure of the US ambassador from the gathering. At 10:50 pm, a group of 15 young guerrillas and their commanders, Pomares and Contreras, entered the house. They killed the minister, who tried to shoot them, during the takeover.[41] The guerrillas received US$2 million ransom, and had their official communiqué read on the radio and printed in the newspaper La Prensa.

Over the next year, the guerrillas got 14 Sandinista prisoners released from jail, and with them were flown to Cuba. One of the released prisoners was Daniel Ortega, who later became president of Nicaragua.[47] The group also lobbied for an increase in wages for National Guard soldiers to 500 córdobas ($71 at the time).[48] The Somoza government responded with further censorship, intimidation, torture, and murder.[49]

In 1975, Somoza imposed a state of siege, censoring the press, and threatening all opponents with internment and torture.[49] Somoza's National Guard also increased its violence against people and communities suspected of collaborating with the Sandinistas. Many of the FSLN guerrillas were killed, including its leader and founder Carlos Fonseca in 1976. Fonseca had returned to Nicaragua in 1975 from his exile in Cuba to try to reunite factions that existed in the FSLN. He and his group were betrayed by someone who informed the National Guard that they were in the area. The guerrilla group was ambushed, and Fonseca was wounded in the process. The next morning the National Guard executed Fonseca.[50]

Split (1977–1978)

[edit]After the FSLN's defeat at the battle of Pancasán in 1967, it adopted the "Prolonged Popular War" (Guerra Popular Prolongada, GPP) theory as its strategic doctrine. The GPP was based on the "accumulation of forces in silence": while the urban organization recruited on the university campuses and robbed money from banks, the main cadres were to permanently settle in the north central mountain zone. There they would build a grassroots peasant support base in preparation for renewed rural guerrilla warfare.[51]

As a consequence of the repressive campaign of the National Guard, in 1975 a group within the FSLN's urban mobilization arm began to question the GPP's viability. In the view of the young orthodox Marxist intellectuals, such as Jaime Wheelock, economic development had turned Nicaragua into a nation of factory workers and wage-earning farm laborers.[52] Wheelock's faction was known as the "Proletarian Tendency".

Shortly after, a third faction arose within the FSLN. The "Insurrectional Tendency", also known as the "Third Way" or Terceristas, led by Daniel Ortega, his brother Humberto Ortega, and Mexican-born Victor Tirado Lopez, was more pragmatic and called for tactical, temporary alliances with non-communists, including the right-wing opposition, in a popular front against the Somoza regime.[53] By attacking the Guard directly, the Terceristas would demonstrate the regime's weakness and encourage others to take up arms.

In October 1977, a group of prominent Nicaraguan professionals, business leaders, and clergymen allied with the Terceristas to form "El Grupo de los Doce" (The Group of Twelve) in Costa Rica. The group's main idea was to organize a provisional government in Costa Rica.[54] The Terceristas' new strategy also included unarmed strikes and rioting by labor and student groups coordinated by the FSLN's "United People's Movement" (Movimiento Pueblo Unido – MPU).

Insurrection (1978)

[edit]On January 10, 1978, Pedro Joaquín Chamorro, the editor of the opposition newspaper La Prensa and leader of the "Democratic Union of Liberation" (Unión Democrática de Liberación – UDEL), was assassinated. His assassins were not identified at the time, but evidence implicated Somoza's son and other members of the National Guard.[55] Spontaneous riots followed in several cities, while the business community organized a general strike demanding Somoza's resignation.

The Terceristas carried out attacks in early February in several Nicaraguan cities. The National Guard responded by further increasing repression and using force to contain and intimidate all government opposition. The nationwide strike that paralyzed the country for ten days weakened private enterprises and most of them decided to suspend their participation in less than two weeks. Meanwhile, Somoza asserted his intention to stay in power until the end of his presidential term in 1981. The United States government showed its displeasure with Somoza by suspending all military assistance to the regime, but continued to approve economic assistance to the country for humanitarian reasons.[56]

In August, the Terceristas took hostages. Twenty-three Tercerista commandos led by Edén Pastora seized the entire Nicaraguan congress and took nearly 1,000 hostages, including Somoza's nephew José Somoza Abrego and cousin Luis Pallais Debayle. Somoza gave in to their demands and paid a $500,000 ransom, released 59 political prisoners (including GPP chief Tomás Borge), broadcast a communiqué with FSLN's call for general insurrection and gave the guerrillas safe passage to Panama.[57]

A few days later six Nicaraguan cities rose in revolt. Armed youths took over the highland city of Matagalpa. Tercerista cadres attacked Guard posts in Managua, Masaya, León, Chinandega and Estelí. Large numbers of semi-armed civilians joined the revolt and put the Guard garrisons of the latter four cities under siege. The September Insurrection of 1978 was subdued at the cost of several thousand, mostly civilian, casualties.[58] Members of all three factions fought in these uprisings, which began to blur the divisions and prepare the way for unified action.[59]

Reunification (1979)

[edit]In early 1979, President Jimmy Carter and the United States ended support for the Somoza government, but did not want a left-wing government to take power in Nicaragua. The moderate "Broad Opposition Front" (Frente Amplio Opositor – FAO), which opposed Somoza, was made up of a conglomeration of dissidents within the government as well as the "Democratic Union of Liberation" (UDEL) and the "Twelve", representatives of the Terceristas (whose founding members included Casimiro A. Sotelo, later to become Ambassador to the U.S. and Canada representing the FSLN). The FAO and Carter came up with a plan to remove Somoza from office but give the FSLN no government power.[60] The FAO's efforts lost political legitimacy, as the grassroots support of the FSLN wanted more structural changes and was opposed to "Somocism without Somoza".[61]

The "Twelve" abandoned the coalition in protest and formed the "National Patriotic Front" (Frente Patriotico Nacional – FPN) together with the "United People's Movement" (MPU). This strengthened the revolutionary organizations as tens of thousands of youths joined the FSLN and the fight against Somoza. A direct consequence of the spread of the armed struggle in Nicaragua was the official reunification of the FSLN that took place March 7, 1979. Nine men, three from each tendency, formed the National Directorate that led the reunited FSLN: Daniel Ortega, Humberto Ortega and Víctor Tirado (Terceristas); Tomás Borge, Bayardo Arce Castaño, and Henry Ruiz (GPP faction); and Jaime Wheelock, Luis Carrión and Carlos Núñez.[59]

Nicaraguan Revolution

[edit]The FSLN evolved from one of many opposition groups to a leadership role in the overthrow of the Somoza regime. By mid-April 1979, five guerrilla fronts opened under the FSLN's joint command, including an internal front in Managua. Young guerrilla cadres and the National Guardsmen were clashing almost daily in cities throughout the country. The Final Offensive's strategic goal was the division of the enemy's forces. Urban insurrection was the crucial element because the FSLN could never hope to outnumber or outgun the National Guard.[62]

On June 4, the FSLN called a general strike, to last until Somoza fell and an uprising was launched in Managua. On June 16, the formation of a provisional Nicaraguan government in exile, consisting of a five-member Junta of National Reconstruction, was announced and organized in Costa Rica. The members of the new junta were Daniel Ortega (FSLN), Moisés Hassán (FPN), Sergio Ramírez (the "Twelve"), Alfonso Robelo (MDN) and Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, the widow of La Prensa's director Pedro Joaquín Chamorro. By the end of that month, with the exception of the capital, most of Nicaragua was under FSLN control, including León and Matagalpa, Nicaragua's two largest cities after Managua.

On July 9, the provisional government in exile released a government program in which it pledged to organize an effective democratic regime, promote political pluralism and universal suffrage, and ban ideological discrimination, except for those promoting the "return of Somoza's rule". On July 17, Somoza resigned, handed over power to Francisco Urcuyo, and fled to Miami. While initially seeking to remain in power to serve out Somoza's presidential term, Urcuyo ceded his position to the junta and fled to Guatemala two days later.

On July 19, the 18th anniversary of the foundation of the FSLN, the FSLN army entered Managua, culminating the first goal of the revolution. The war left 30,000–50,000 dead and 150,000 Nicaraguans in exile. The five-member junta entered Managua the next day and assumed power, reiterating its pledge to work for political pluralism, a mixed economic system, and a nonaligned foreign policy.[63]

Sandinista rule (1979–1990)

[edit]The Sandinistas inherited a country with a debt of US$1.6 billion, an estimated 30,000 to 50,000 war dead, 600,000 homeless, and a devastated economic infrastructure.[64][65] To begin establishing a new government, they created a Council (or junta) of National Reconstruction, made up of five appointed members. Three of the appointed members—Sandinista militants Daniel Ortega, Moisés Hassán, and novelist Sergio Ramírez (a member of Los Doce "the Twelve")—belonged to the FSLN. Two opposition members, businessman Alfonso Robelo, and Violeta Barrios de Chamorro (the widow of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro), were also appointed. Only three votes were needed to pass law.

The FSLN also established a Council of State, subordinate to the junta, which was composed of representative bodies. But the Council of State gave political parties only 12 of 47 seats; the rest were given to Sandinista organizations.[66] Of the 12 seats reserved for political parties, only three were not allied with the FSLN.[66] Due to the rules governing the Council of State, in 1980 both non-FSLN junta members resigned. Nevertheless, as of the 1982 State of Emergency, opposition parties were no longer given representation in the council.[66] The preponderance of power also remained with the Sandinistas through their mass organizations, including the Sandinista Workers' Federation (Central Sandinista de Trabajadores), the Luisa Amanda Espinoza Nicaraguan Women's Association (Asociación de Mujeres Nicaragüenses Luisa Amanda Espinoza), the National Union of Farmers and Ranchers (Unión Nacional de Agricultores y Ganaderos), and most importantly the Sandinista Defense Committees (CDS). The Sandinista-controlled mass organizations were extremely influential over civil society and saw their power and popularity peak in the mid-1980s.[66]

Upon assuming power, the FSLN's official political platform included nationalization of property owned by the Somozas and their supporters; land reform; improved rural and urban working conditions; free unionization for all workers, both urban and rural; price fixing for commodities of basic necessity; improved public services, housing conditions, education; abolition of torture, political assassination and the death penalty; protection of democratic liberties; equality for women; non-aligned foreign policy; and formation of a "popular army" under the leadership of the FSLN and Humberto Ortega.

The FSLN's literacy campaign sent teachers into the countryside; within six months, half a million people had been taught rudimentary reading, bringing the national illiteracy rate down from over 50% to just under 12%.[dubious – discuss] Over 100,000 Nicaraguans participated as literacy teachers. One of the literacy campaign's aims was to create a literate electorate that could make informed choices in the promised elections. The success of the literacy campaign was recognized by UNESCO with a Nadezhda Krupskaya International Prize, although the actual success of this literary campaign, and its long-term impact, have been called into question.[67]

The FSLN also created neighborhood groups similar to the Cuban Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, called Sandinista Defense Committees (Comités de Defensa Sandinista or CDS). Especially in the early days following Somoza's overthrow, the CDSes served as de facto units of local governance. Their obligations included political education, organizing Sandinista rallies, distributing food rations, organizing neighborhood/regional cleanup and recreational activities, policing to control looting, and apprehending counter-revolutionaries. The CDSes organized civilian defense efforts against Contra activities and a network of intelligence systems in order to apprehend their supporters. These activities led critics of the Sandinistas to argue that the CDS was a system of local spy networks for the government used to stifle political dissent, and the CDS did hold limited powers—such as the ability to suspend privileges such as driver licenses and passports—if locals refused to cooperate with the government. After the initiation of heavier U.S. military involvement in the Nicaraguan conflict the CDS was empowered to enforce wartime bans on political assembly and association with other political parties (i.e., parties associated with the Contras).[citation needed]

By 1980, conflicts began to emerge between the Sandinista and non-Sandinista members of the governing junta. Violeta Chamorro and Alfonso Robelo resigned from the junta in 1980, and rumors began that members of the Ortega junta would consolidate power among themselves. These allegations spread, and rumors intensified that it was Ortega's goal to turn Nicaragua into a state modeled after Cuban socialism. In 1979 and 1980, former Somoza supporters and ex-members of Somoza's National Guard formed irregular military forces, while the original core of the FSLN began to splinter. Armed opposition to the Sandinista government eventually divided into two main groups: The Fuerza Democrática Nicaragüense (FDN), a U.S.-supported army formed in 1981 by the CIA, U.S. State Department, and former members of the Somoza-era Nicaraguan National Guard; and the Alianza Revolucionaria Democratica (ARDE) Democratic Revolutionary Alliance, a group that had existed since before the FSLN and was led by Sandinista founder and former FSLN supreme commander Edén Pastora, a.k.a. "Commander Zero".[68] Milpistas, former anti-Somoza rural militias, eventually formed the largest pool of recruits for the Contras. Although independent and often in conflict with each other, these guerrilla bands—along with several others—all became known as Contras (short for contrarrevolucionarios—counter-revolutionaries).[69]

The opposition militias were initially organized and largely remained segregated according to regional affiliation and political backgrounds. They conducted attacks on economic, military, and civilian targets. During the Contra war, the Sandinistas arrested suspected members of the Contra militias and censored publications they accused of collaborating with the enemy, such as the U.S., the FDN, and ARDE.

State of Emergency (1982–1988)

[edit]In March 1982 the Sandinistas declared an official State of Emergency. They argued that this was a response to attacks by counter-revolutionary forces.[70] The State of Emergency lasted six years, until January 1988, when it was lifted.

Under the new "Law for the Maintenance of Order and Public Security" the "Tribunales Populares Anti-Somocistas" allowed for the indefinite holding of suspected counter-revolutionaries without trial. The State of Emergency, however, most notably affected rights and guarantees contained in the "Statute on Rights and Guarantees of Nicaraguans".[71] Many civil liberties were curtailed or canceled such as the freedom to organize demonstrations, the inviolability of the home, freedom of the press, freedom of speech, and the freedom to strike.[71]

All independent news program broadcasts were suspended. In total, twenty-four programs were cancelled. In addition, Sandinista censor Nelba Cecilia Blandón issued a decree ordering all radio stations to take broadcasts from government radio station La Voz de La Defensa de La Patria every six hours.[72]

The rights affected also included certain procedural guarantees in the case of detention including habeas corpus.[71] The State of Emergency was not lifted during the 1984 elections. There were many instances where rallies of opposition parties were physically broken up by Sandinista Youth or pro-Sandinista mobs. Opponents to the State of Emergency argued its intent was to crush resistance to the FSLN. James Wheelock justified the actions of the Directorate by saying "... We are annulling the license of the false prophets and the oligarchs to attack the revolution."[73]

Some emergency measures were taken before 1982. In December 1979 special courts called "Tribunales Especiales" were established to speed up the processing of 7,000-8,000 National Guard prisoners. These courts operated through relaxed rules of evidence and due process and were often staffed by law students and inexperienced lawyers. However, the decisions of the "Tribunales Especiales" were subject to appeal in regular courts. Many of the National Guard prisoners were released immediately due to lack of evidence. Others were pardoned or released by decree. By 1986 only 2,157 remained in custody and only 39 were still being held in 1989 when they were released under the Esquipulas II agreement.[71]

On October 5, 1985, the Sandinistas broadened the 1982 State of Emergency and suspended many more civil rights. A new regulation also forced any organization outside of the government to first submit any statement it wanted to make public to the censorship bureau for prior approval.[74]

The FSLN lost power in the presidential election of 1990 when Daniel Ortega was defeated in an election for the Presidency of Nicaragua by Violeta Chamorro.

Sandinistas vs. Contras

[edit]

Upon assuming office in 1981, U.S. President Ronald Reagan condemned the FSLN for joining with Cuba in supporting "Marxist" revolutionary movements in other Latin American countries such as El Salvador. His administration authorized the CIA to begin financing, arming and training rebels, most of whom were the remnants of Somoza's National Guard, as anti-Sandinista guerrillas that were branded "counter-revolutionary" by leftists (contrarrevolucionarios in Spanish).[75] This was shortened to Contras, a label the force chose to embrace. Edén Pastora and many of the indigenous guerrilla forces, who were not associated with the "Somocistas", also resisted the Sandinistas.

The Contras operated out of camps in the neighboring countries of Honduras to the north and Costa Rica (see Edén Pastora cited below) to the south. As was typical in guerrilla warfare, they were engaged in a campaign of economic sabotage in an attempt to combat the Sandinista government and disrupted shipping by planting underwater mines in Nicaragua's Corinto harbour,[76] an action condemned by the International Court of Justice as illegal. The U.S. also sought to place economic pressure on the Sandinistas, and, as with Cuba, the Reagan administration imposed a full trade embargo.[77]

The Contras also carried out a systematic campaign to disrupt the social reform programs of the government. This campaign included attacks on schools, health centers and the majority of the rural population that was sympathetic to the Sandinistas. Widespread murder, rape, and torture were also used as tools to destabilize the government and to "terrorize" the population into collaborating with the Contras. Throughout this campaign, the Contras received military and financial support from the CIA and the Reagan Administration.[78] This campaign has been condemned internationally for its many human rights violations. Contra supporters have often tried to downplay these violations, or countered that the Sandinista government carried out much more. In particular, the Reagan administration engaged in a campaign to alter public opinion on the Contras that has been termed "white propaganda".[79] In 1984, the International Court of Justice judged that the United States Government had been in violation of International law when it supported the Contras.[80]

After the U.S. Congress prohibited federal funding of the Contras through the Boland Amendment in 1983, the Reagan administration continued to back the Contras by raising money from foreign allies and covertly selling arms to Iran (then engaged in a war with Iraq), and channelling the proceeds to the Contras (see the Iran–Contra affair).[81] When this scheme was revealed, Reagan admitted that he knew about Iranian "arms for hostages" dealings but professed ignorance about the proceeds funding the Contras; for this, National Security Council aide Lt. Col. Oliver North took much of the blame.

Senator John Kerry's 1988 U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations report on links between the Contras and drug imports to the US concluded that "senior U.S. policy makers were not immune to the idea that drug money was a perfect solution to the Contras' funding problems".[82] According to the National Security Archive, Oliver North had been in contact with Manuel Noriega, the US-backed president of Panama. The Reagan administration's support for the Contras continued to stir controversy well into the 1990s. In August 1996, San Jose Mercury News reporter Gary Webb published a series titled Dark Alliance,[83] linking the origins of crack cocaine in California to the CIA-Contra alliance. Webb's allegations were repudiated by reports from the Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, and The Washington Post, and the San Jose Mercury News eventually disavowed his work.[84] An investigation by the United States Department of Justice also stated that their "review did not substantiate the main allegations stated and implied in the Mercury News articles".[85] Regarding the specific charges towards the CIA, the DOJ wrote "the implication that the drug trafficking by the individuals discussed in the Mercury News articles was connected to the CIA was also not supported by the facts".[85] The CIA also investigated and rejected the allegations.[86]

The Contra war unfolded differently in the northern and southern zones of Nicaragua. Contras based in Costa Rica operated on Nicaragua's Caribbean coast, which is sparsely populated by indigenous groups including the Miskito, Sumo, Rama, Garifuna, and Mestizo. Unlike Spanish-speaking western Nicaragua, the Caribbean Coast also has lots of speakers of indigenous languages and English-based creoles, and was largely ignored by the Somoza regime. The costeños did not participate in the uprising against Somoza and viewed Sandinismo with suspicion from the outset.[87]

Elections

[edit]1984 election

[edit]While the Sandinistas encouraged grassroots pluralism, they were perhaps less enthusiastic about national elections. They argued that popular support was expressed in the insurrection and that further appeals to popular support would be a waste of scarce resources.[88] International pressure and domestic opposition eventually pressed the government toward a national election.[88] Tomás Borge warned that the elections were a concession, an act of generosity and of political necessity.[89] On the other hand, the Sandinistas had little to fear from the election given the advantages of incumbency and the restrictions on the opposition, and they hoped to discredit the armed efforts to overthrow them.[90]

A broad range of political parties, ranging in political orientation from far-left to far-right, competed for power.[91] Following promulgation of a new populist constitution, Nicaragua held national elections in 1984. Independent electoral observers from around the world—including groups from the UN as well as observers from Western Europe—claimed that the elections had been fair.[92] Several groups, however, disputed this, including UNO, a broad coalition of anti-Sandinista activists, COSEP, an organization of business leaders, the Contra group "FDN", organized by former Somozan-era National Guardsmen, landowners, businessmen, peasant highlanders, and what some claimed as their patron, the U.S. government.[93]

Although initially willing to stand in the 1984 elections, the UNO, headed by Arturo Cruz (a former Sandinista), declined participation in the elections based on their own objections to the restrictions placed on the electoral process by the State of Emergency and the official advisement of President Ronald Reagan's State Department, who wanted to de-legitimize the election process. Among other parties that abstained was COSEP, who had warned the FSLN that they would decline participation unless freedom of the press was reinstituted. Coordinadora Democrática (CD) also refused to file candidates and urged Nicaraguans not to take part in the election. The Independent Liberal Party (PLI), headed by Virgilio Godoy Reyes, announced its refusal to participate in October.[94] Consequently, when the elections went ahead the U.S. raised objections based upon political restrictions instituted by the State of Emergency (e.g., censorship of the press, cancellation of habeas corpus, and the curtailing of free assembly).

Daniel Ortega and Sergio Ramírez were elected president and vice-president, and the FSLN won an overwhelming 61 out of 96 seats in the new National Assembly, having taken 67% of the vote on a turnout of 75%.[94] Despite international validation of the elections by multiple political and independent observers (virtually all from among U.S. allies), the United States refused to recognize the elections, with President Ronald Reagan denouncing the elections as a sham. Daniel Ortega began his six-year presidential term on January 10, 1985. After the United States Congress turned down continued funding of the Contras in April 1985, the Reagan administration ordered a total embargo on United States trade with Nicaragua the following month, accusing the Sandinista government of threatening United States security in the region.[94]

1990 election

[edit]The elections of 1990, which had been mandated by the constitution passed in 1987, saw the Bush administration funnel $49.75 million of 'non-lethal' aid to the Contras, as well as $9 million to the opposition UNO—equivalent to $2 billion worth of intervention by a foreign power in a US election at the time, and proportionately five times the amount George Bush had spent on his own election campaign.[95][96] When Violeta Chamorro visited the White House in November 1989, the US pledged to maintain the embargo against Nicaragua unless Violeta Chamorro won.[97]

There were reports of intimidation and violence during the election campaign by the contras,[98] with a Canadian observer mission claiming that 42 people were killed by the contras in "election violence" in October 1989.[99] Sandinistas were also accused of intimidation and violence during the election campaign. According to the Puebla Institute, by mid-December 1989, seven opposition leaders had been murdered, 12 had disappeared, 20 had been arrested, and 30 others assaulted. In late January 1990, the OAS observer team reported that "a convoy of troops attacked four truckloads of UNO sympathizers with bayonets and rifle butts, threatening to kill them."[100]

Years of conflict had left 50,000 casualties and $12 billion of damages in a society of 3.5 million people and an annual GNP of $2 billion. After the election, a survey was taken of voters: 75.6% agreed that if the Sandinistas had won, the war would never have ended. 91.8% of those who voted for the UNO agreed with this (William I Robinson, op cit).[101] The Library of Congress Country Studies on Nicaragua states:

Despite limited resources and poor organization, the UNO coalition under Violeta Chamorro directed a campaign centered around the failing economy and promises of peace. Many Nicaraguans expected the country's economic crisis to deepen and the Contra conflict to continue if the Sandinistas remained in power. Chamorro promised to end the unpopular military draft, bring about democratic reconciliation, and promote economic growth. In the February 25, 1990, elections, Violeta Barrios de Chamorro carried 55 percent of the popular vote against Daniel Ortega's 41 percent.[94]

Opposition (1990–2006)

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2017) |

In 1987, due to a stalemate with the Contras, the Esquipulas II treaty was brokered by Costa Rican President Óscar Arias Sánchez. The treaty's provisions included a call for a cease-fire, freedom of expression, and national elections. After the February 26, 1990 elections, the Sandinistas lost and peacefully passed power to the National Opposition Union (UNO), an alliance of 14 opposition parties ranging from the conservative business organization COSEP to Nicaraguan communists. UNO's candidate, Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, replaced Daniel Ortega as president of Nicaragua.

Reasons for the Sandinista loss in 1990 are disputed. Defenders of the defeated government assert that Nicaraguans voted for the opposition due to the continuing U.S. economic embargo and potential Contra threat. Others have alleged that the United States threatened to continue to support the Contras and continue the civil war if the regime was not voted out of power.[102]

After their loss, the Sandinista leaders held most of the private property and businesses that had been confiscated and nationalized by the FSLN government. This process became known as the "piñata" and was tolerated by the new Chamorro government. Ortega also claimed to "rule from below" through groups he controls such as labor unions and student groups.

Ortega remained the head of the FSLN, but his brother Humberto resigned from the party and remained at the head of the Sandinista Army, becoming a close confidante and supporter of Chamorro. The party also experienced internal divisions, with prominent Sandinistas such as Ernesto Cardenal and Sergio Ramírez resigning to protest what they described as heavy-handed domination of the party by Daniel Ortega. Ramírez also founded a separate political party, the Sandinista Renovation Movement (MRS); his faction came to be known as the renovistas, who favor a more social democratic approach than the ortodoxos, or hardliners. In the 1996 Nicaraguan election, Ortega and Ramírez both campaigned unsuccessfully as presidential candidates on behalf of their respective parties, with Ortega receiving 43% of the vote while Arnoldo Alemán of the Constitutional Liberal Party received 51%. The Sandinistas won second place in the congressional elections, with 36 of 93 seats.

Ortega was re-elected as leader of the FSLN in 1998. Municipal elections in November 2000 saw a strong Sandinista vote, especially in urban areas, and former Tourism Minister Herty Lewites was elected mayor of Managua. This result led to expectations of a close race in the presidential elections scheduled for November 2001. Daniel Ortega and Enrique Bolaños of the Constitutional Liberal Party (PLC) ran neck-and-neck in the polls for much of the campaign, but in the end the PLC won a clear victory. The results of these elections were that the FSLN won 42.6% of the vote for parliament (versus 52.6% for the PLC), giving them 41 out of the 92 seats in the National Assembly (versus 48 for the PLC). In the presidential race, Ortega lost to Bolaños 46.3% to 53.6%.

Daniel Ortega was once again re-elected as leader of the FSLN in March 2002 and re-elected as president of Nicaragua in November 2006.

Return to government

[edit]In 2006, Daniel Ortega was elected president with 38% of the vote (see 2006 Nicaraguan general election). This occurred despite the fact that the breakaway Sandinista Renovation Movement continued to oppose the FSLN, running former Mayor of Managua Herty Lewites as its candidate for president. However, Lewites died several months before the elections.

The FSLN also won 38 seats in the congressional elections, becoming the party with the largest representation in parliament. The split in the Constitutionalist Liberal Party helped to allow the FSLN to become the largest party in Congress. The Sandinista vote was also split between the FSLN and MRS, but the split was more uneven, with limited support for the MRS. The vote for the two liberal parties combined was larger than the vote for the two Sandinista parties. In 2010, several liberal congressmen raised accusations about the FSLN presumably attempting to buy votes in order to pass constitutional reforms that would allow Ortega to run for office for the 6th time since 1984.[103] In 2011, Ortega was re-elected as president.[104]

Ortega was allowed by Nicaraguan Supreme Court to run again as president, despite having already served two mandates, in a move which was strongly criticized by the opposition. The Supreme Court also banned the leader of the Independent Liberal Party Eduardo Montealegre from running in the election. Ortega was re-elected as president, amid claims of electoral fraud; data about turnout were unclear: while the Supreme Electoral Council claimed a turnout of 66% of voters, the opposition claimed only 30% of voters actually went to the polls.[105]

2018–20 protests

[edit]The year 2018 was marked by particular unrest in Nicaragua that had not been seen in the country in three decades. It came in two different phases, with initial unrest in the context of a fire at the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve in the Río San Juan department (which came to an end when rain abruptly put the fire out), leading on to an outbreak of violence a few weeks later after social security reforms were announced by the government.

During this unrest there were many deaths linked to the violence, as well as many instances of torture, sexual assaults, death threats, ransacking and burning of buildings and violence against journalists. Opposition figures argued that the government was responsible for the violence, a view supported by some press outlets and NGOs such as Amnesty International.[106][107] Many opposition figures and independent journalists have been arrested and police raids of opposition forces and independent media have occurred frequently.[108]

On September 29, 2018, President Ortega declared that the protests were illegal, stating that demonstrators would "respond to justice."[109] The United Nations condemned the actions as being a violation of human rights regarding freedom of assembly.[109]

Carlos Fernando Chamorro, son of former president Violeta Chamorro and editor of Confidencial, left the country after his office was subject to police search in December 2018.[110]

In December 2018, the government revoked the licenses of five human rights organizations, closed the offices of the cable news and online show Confidencial, and beat journalists when they protested.[111]

The Confidential newspaper and other media were seized and taken by the government of Daniel Ortega[112] Several service stations of the Puma brand were closed on the afternoon, December 20, by representatives of the Nicaraguan Energy Institute (INE), a state entity that has the mandate to regulate, among others, the hydrocarbons sector. Puma Energy entered the Nicaraguan oil and fuel derivatives market at the end of March 2011, when it bought the entire network of Esso stations in Nicaragua, as part of a regional operation that involved the purchase of 290 service stations and eight storage terminals of fuel in four countries of Central America.[113]

On December 21, 2018, the Nicaraguan police raided the offices of the 100% News Channel. They arrested Miguel Mora, owner of the Canal; Lucía Pineda, Head of Press of 100% Noticias and Verónica Chávez, wife of Miguel Mora and host of the Ellas Lo Dicen Program. Subsequently, Verónica Chávez was released. Miguel Mora and Lucia Pineda were accused of terrorist crimes and provoking hatred and discrimination between the police and Sandinistas.[114]

On January 30, 2019, the FSLN was expelled from the Socialist International, which cited "gross violations of human rights and democratic values committed by the government of Nicaragua".[115][116] The ruling Democratic Revolutionary Party of Panama, also a member of the Socialist International, rejected the expulsion of the FSLN and threatened to leave the International, saying that it has abandoned its principles and made a decision regarding Latin America without consulting the Latin American parties, and referred to a "history of brotherhood in the struggle for social justice in Central America" between the two parties.[117]

Ideology

[edit]Through the media and the works of FSLN leaders such as Carlos Fonseca, the life and times of Augusto César Sandino became its unique symbol in Nicaragua. The ideology of Sandinismo gained momentum in 1974, when a Sandinista-initiated hostage situation resulted in the Somoza government adhering to FSLN demands and publicly printing and airing work on Sandino in well known newspapers and media outlets.

During the struggle against Somoza, the FSLN leaders' internal disagreements over strategy and tactics were reflected in three main factions:

- The guerra popular prolongada (GPP, "protracted people's war") faction was rural-based and sought long-term "silent accumulation of forces" within the country's large peasant population, which it saw as the main social base for the revolution.

- The tendencia proletaria (TP, "proletarian tendency"), led by Jaime Wheelock, reflected an orthodox Marxist approach that sought to organize urban workers.

- The tercerista/insurreccionista (TI, "third way/insurrectionist") faction, led by Humberto, Casimiro A. Sotelo, and Daniel Ortega, was ideologically eclectic, favoring a more rapid insurrectional strategy in alliance with diverse sectors of the country, including business owners, churches, students, the middle class, unemployed youth and the inhabitants of shantytowns. The terceristas also helped attract popular and international support by organizing a group of prominent Nicaraguan professionals, business leaders, and clergymen (known as "the Twelve"), who called for Somoza's removal and sought to organize a provisional government from Costa Rica.

Nevertheless, while ideologies varied between FSLN leaders, all leaders essentially agreed that Sandino provided a path for the Nicaragua masses to take charge, and the FSLN would act as the legitimate vanguard. The extreme end of the ideology links Sandino to Roman Catholicism and portrays him as descending from the mountains in Nicaragua knowing he would be betrayed and killed. Generally however, most Sandinistas associated Sandino on a more practical level, as a heroic and honest person who tried to combat the evil forces of imperialist national and international governments that existed in Nicaragua's history.

An important part of the Sandinista ideology is Christian socialism and liberation theology. This connection was so strong that Catholic priest Ernesto Cardenal who served as the Minister of Culture in the Sandinista government, remarked: "I think Nicaraguans who separate Christianity from Revolution are mistaken. Here they are the same thing."[118] In response to the growing radicalization and opposition to Somoza amongst the Church, the FSLN incorporated a Catholic message into its program; this was augmented by left-wing Catholic organizations such as the Movimiento Cristiano Revolucionario joining the FSLN, whose members would assume high responsibilities within the Sandinista government.[119] Sandinista activists infiltrated folk and religious imagery - on one such instance, they distributed paintings of the resurrection of Christ, where Christ appeared in a black and red cape (Sandinista colours), which bore the letters FSLN. As the FSLN lacked party structures which could be used for organizing, they relied on friendly clergymen instead; according to Peter Marchetti, this relationship became so intimate that "the parish replaced Lenin's idea of a cell".[118] Sandinista Minister of Education Carlos Tünnerman argued that Sandinismo "is deeply rooted in Christianity" and "came about through a process of Christian self-reflection".[120]

As Sandinistas relied on churches to build their structures, their ideological relationship to Catholicism was not just based on mutual support, but on active incorporation of Political Catholicism. Sandinista musician Carlos Mejía Godoy composed "Misa Campesina Nicaraguense" (Nicaraguan peasant mass) which replaced the traditional mass in Nicaraguan churches, with Catholic hymns praising "worker Christ". The FSLN provided churches with decals of Virgin Mary and Catholic saints next to portraits of Augusto Sandino, Che Guevara and Camilo Torres Restrepo.[118] Sandinistas openly promoted the Catholic concept of "preferential option for the poor",[121] and the Secretary-General of FSLN Carlos Fonseca remarked: "Since I began working with the Sandinista Front I have never—never! at any moment met anything which contradicts my Christian faith, nor which clashes with my Christian morality. Never. Just the opposite. For me the Sandinista Front has been the channel that has enabled me to live my Christian faith more authentically, that is, with actions."[118] Sandinismo offered a blend of the Marxist notion of class struggle and liberation theology, presenting their ideology as an 'extension' of Catholicism. Tomás Borge argued that the Sandinista revolution "was on behalf of all human beings, but as with Christ above all for the poor."[122]

Principles of government

[edit]For purposes of making sense of how to govern, the FSLN drew four fundamental principles from the work of Carlos Fonseca and his understanding of the lessons of Sandino. According to Bruce E. Wright, "the Governing Junta of National Reconstruction agreed, under Sandinista leadership, that these principles had guided it in putting into practice a form of government that was characterized by those principles."[123] It is generally accepted that these following principles have evolved the "ideology of Sandinismo".[124] Three of these (excluding popular participation, which was presumably contained in Article 2 of the Constitution of Nicaragua) were to ultimately be guaranteed by Article 5 of the Constitution of Nicaragua. They are as follows:

- Political Pluralism – The ultimate success of the Sandinista Front in guiding the insurrection and in obtaining the leading fore within it was based on the fact that the FSLN, through the tercerista guidance, had worked with many sectors of the population in defeating the Somoza dictatorship. The FSLN and all those who would constitute the new provisional government were called diverse; "they were plural in virtually all senses".[125]

- Mixed Economy – Fonseca's understanding that Nicaragua was not, in spite of Browderist interpretations, simply a feudal country and that it had also never really developed its own capitalism made it clear that a simple feudalism-capitalism-socialism path was not a rational way to think about the future development of Nicaragua. The FSLN was not necessarily seen simply as the vanguard of the proletariat revolution. The proletariat was but a minor fraction of the population. A complex class structure in a revolution based on unity among people from various class positions suggested more that it made sense to see the FSLN as the "vanguard of the people".

- Popular Participation and Mobilization – This calls for more than simple representative democracy. The inclusion of the mass organizations in the Council of State clearly manifested this conception. In Article 2 of the Constitution this is spelled out as follows: "The people exercise democracy, freely participating and deciding in the construction of the economic, political and social system what is most appropriate to their interest. The people exercise power directly and by their means of their representatives, freely elected in accord with universal, equal, direct, free, and secret suffrage."[126]

- International Non-alignment – This is a result of the fundamentally Bolivarist conceptions of Sandino as distilled through the modern understanding of Fonseca. The U.S. government and large U.S. economic entities were a significant part of the problem for Nicaragua. But experiences with the traditional parties allied with the Soviet Union had also been unsatisfactory. Thus it was clear that Nicaragua must seek its own road.

Bruce E. Wright claims that "this was a crucial contribution from Fonseca's work that set the template for FSLN governance during the revolutionary years and beyond".[125]

Policies and programs

[edit]Foreign policy

[edit]Cuban assistance

[edit]Beginning in 1967, the Cuban General Intelligence Directorate, or DGI, had begun to establish ties with Nicaraguan revolutionary organizations. By 1970 the DGI had managed to train hundreds of Sandinista guerrilla leaders and had vast influence over the organization. After the successful ousting of Somoza, DGI involvement in the new Sandinista government expanded rapidly. An early indication of the central role that the DGI would play in the Cuban-Nicaraguan relationship is a meeting in Havana on July 27, 1979, at which diplomatic ties between the two countries were re-established after more than 25 years. Julián López Díaz, a prominent DGI agent, was named Ambassador to Nicaragua. Cuban military and DGI advisors, initially brought in during the Sandinista insurgency, would swell to over 2,500 and operated at all levels of the new Nicaraguan government.

The Cubans would like to have helped more in the development of Nicaragua towards socialism. Following the US invasion of Grenada, countries previously looking for support from Cuba saw that the United States was likely to take violent action to discourage this.

Cuban assistance after the revolution

[edit]The early years of the Nicaraguan revolution had strong ties to Cuba. The Sandinista leaders acknowledged that the FSLN owed a great debt to the socialist island. Once the Sandinistas assumed power, Cuba gave Nicaragua military advice, as well as aid in education, health care, vocational training and industry building for the impoverished Nicaraguan economy. In return, Nicaragua provided Cuba with grains and other foodstuffs to help Cuba overcome the effects of the US embargo.

Relationship with eastern bloc intelligence agencies

[edit]Pre-Revolution

[edit]According to Cambridge University historian Christopher Andrew, who undertook the task of processing the Mitrokhin Archive, Carlos Fonseca Amador, one of the original three founding members of the FSLN had been recruited by the KGB in 1959 while on a trip to Moscow. This was one part of Aleksandr Shelepin's 'grand strategy' of using national liberation movements as a spearhead of the Soviet Union's foreign policy in the Third World, and in 1960 the KGB organized funding and training for twelve individuals that Fonseca handpicked. These individuals were to be the core of the new Sandinista organization. In the following several years, the FSLN tried with little success to organize guerrilla warfare against the government of Luis Somoza Debayle. After several failed attempts to attack government strongholds and little initial support from the local population, the National Guard nearly annihilated the Sandinistas in a series of attacks in 1963. Disappointed with the performance of Shelepin's new Latin American "revolutionary vanguard", the KGB reconstituted its core of the Sandinista leadership into the ISKRA group and used them for other activities in Latin America.

According to Andrew, Mitrokhin says during the following three years the KGB handpicked several dozen Sandinistas for intelligence and sabotage operations in the United States. Andrew and Mitrokhin say that in 1966, this KGB-controlled Sandinista sabotage and intelligence group was sent to northern Mexico near the US border to conduct surveillance for possible sabotage.[127]

In July 1961 during the Berlin Crisis of 1961 KGB chief Alexander Shelepin sent a memorandum to Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev containing proposals to create a situation in various areas of the world which would favor dispersion of attention and forces by the US and their satellites, and would tie them down during the settlement of the question of a German peace treaty and West Berlin. It was planned, inter alia, to organize an armed mutiny in Nicaragua in coordination with Cuba and with the "Revolutionary Front Sandino". Shelepin proposed to make appropriations from KGB funds in addition to the previous assistance $10,000 for purchase of arms.

Khrushchev sent the memo with his approval to his deputy Frol Kozlov and on August 1 it was, with minor revisions, passed as a CPSU Central Committee directive. The KGB and the Soviet Ministry of Defense were instructed to work out more specific measures and present them for consideration by the Central Committee.[128]

Cooperation with foreign intelligence agencies during the 1980s

[edit]Other researchers have documented the contribution made from other Warsaw Pact intelligence agencies to the fledgling Sandinista government including the East German Stasi, by using recently declassified documents from Berlin[129] as well as from former Stasi spymaster Markus Wolf who described the Stasi's assistance in the creation of a secret police force modeled on East Germany's.[130]

Educational assistance

[edit]Cuba was instrumental in the Nicaraguan Literacy Campaign. Nicaragua was a country with a very high rate of illiteracy, but the campaign succeeded in lowering the rate from 50% to 12%. The revolution in Cuban education since the ousting of the US-backed Batista regime not only served as a model for Nicaragua but also provided technical assistance and advice. Cuba played an important part in the Campaign, providing teachers on a yearly basis after the revolution. Prevost states that "Teachers were not the only ones studying in Cuba, about 2,000 primary and secondary students were studying on the Isle of Youth and the cost was covered by the host country (Cuba)".[131]

1980 literacy campaign

[edit]

The goals of the 1980 Literacy Campaign were socio-political, strategic as well as educational. It was the most prominent campaign with regards to the new education system. Illiteracy in Nicaragua was reduced, and it has been claimed that overall illiteracy went down from 50% to 13%[dubious – discuss], although this figure has been called into question.[67] One of the government's major concerns was the previous education system under the Somoza regime which did not see education as a major factor on the development of the country. As mentioned in the Historical Program of the FSLN of 1969, education was seen as a right and the pressure to stay committed to the promises made in the program was even stronger. 1980 was declared the "Year of Literacy" and the major goals of the campaign that started only 8 months after the FSLN took over. This included the eradication of illiteracy and the integration of different classes, races, gender and age. Political awareness and the strengthening of political and economic participation of the Nicaraguan people was also a central goal of the Literacy Campaign. The campaign was a key component of the FSLN's cultural transformation agenda.

The basic reader which was disseminated and used by teacher was called "Dawn of the People" based on the themes of Sandino, Carlos Fonseca, and the Sandinista struggle against imperialism and defending the revolution. Political education was aimed at creating a new social values based on the principles of Sandinista socialism, such as social solidarity, worker's democracy, egalitarianism, and anti-imperialism.[132][133][134][135][136]

Health care

[edit]Health conditions in Somoza era Nicaragua were abysmal according to a report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.[137] Vaccine coverage of babies under a year old was 88% immunised against polio and 78% against measles in 1983.[138] Despite the turmoil caused by the Contra War under-fire mortality was reduced by approximately half during this period.[139]

In this area Cuba played a role by again offering expertise to Nicaragua. Over 1,500 Cuban doctors worked in Nicaragua and provided more than five million consultations. Cuban personnel were essential in the elimination of polio, the decrease in whooping cough, rubella, measles and the lowering of the infant mortality rate. Gary Prevost states that Cuban personnel made it possible for Nicaragua to have a national health care system that reached the majority of its citizens.[140]

Vocational assistance

[edit]Cuba has participated in the training of Nicaraguan workers in the use of new machinery imported to Nicaragua. The Nicaraguan revolution caused the United States to oppose the country's government; therefore the Sandinistas would not receive any aid from the United States. The United States embargo against Nicaragua, imposed by the Reagan administration in May 1985,[141] made it impossible for Nicaragua to receive spare parts for US-made machines, so this led Nicaragua to look to other countries for help. Cuba was the best choice because of the shared language and proximity and also because it had imported similar machinery over the years. Nicaraguans went to Cuba for short periods of three to six months and this training involved close to 3,000 workers.[131] Countries such as the UK, sent farm equipment to Nicaragua.[142]

Industry and infrastructure

[edit]Cuba helped Nicaragua in large projects such as building roads, power plants and sugar mills. Cuba also attempted to help Nicaragua build the first overland route linking Nicaragua's Atlantic and Pacific coasts. The road was meant to traverse 420 kilometres (260 mi) of jungle, but completion of the road and usage was hindered by the Contra war, and it was never completed.[citation needed]

Another significant feat was the building of the Tipitapa-Malacatoya sugar mill. It was completed and inaugurated during a visit by Fidel Castro in January 1985. The plant used the newest technology available and was built by workers trained in Cuba. Also during this visit Castro announced that all debts incurred on this project were absolved.[140] Cuba also provided technicians to aid in the sugar harvest and assist in the rejuvenation of several old sugar mills. Cubans also assisted in building schools and similar projects.[citation needed]

Ministry of Culture

[edit]After the Nicaraguan revolution, the Sandinista government established a Ministry of Culture in 1980. The ministry was spearheaded by Ernesto Cardenal, a poet and priest. The ministry was established in order to socialize the modes of cultural production.[143] This extended to art forms including dance, music, art, theatre and poetry.[143] The project was created to democratize culture on a national level.[144] The aim of the ministry was to "democratize art" by making it accessible to all social classes as well as protecting the right of the oppressed to produce, distribute and receive art.[143] In particular, the ministry was devoted to the development of working class and campesino, or peasant culture.[143] Therefore, the ministry sponsored cultural workshops throughout the country until October 1988 when the Ministry of Culture was integrated into the Ministry of Education because of financial troubles.[145]

The objective of the workshops was to recognize and celebrate neglected forms of artistic expression.[143] The ministry created a program of cultural workshops known as, Casas de Cultura and Centros Populares de Cultura.[144] The workshops were set up in poor neighbourhoods and rural areas and advocated universal access and consumption of art in Nicaragua.[143] The ministry assisted in the creation of theatre groups, folklore and artisanal production, song groups, new journals of creation and cultural criticism, and training programs for cultural workers.[144] The ministry created a Sandinista daily newspaper named Barricada and its weekly cultural addition named Ventana along with the Television Sandino, Radio Sandino and the Nicaraguan film production unit called the INCINE.[144] There were existing papers which splintered after the revolution and produced other independent, pro-Sandinista newspapers, such as El Nuevo Diario and its literary addition Nuevo Amanecer Cultural.[144] Editorial Nueva Nicaragua, a state publishing house for literature, was also created.[144] The ministry collected and published political poetry of the revolutionary period, known as testimonial narrative, a form of literary genre that recorded the experiences of individuals in the course of the revolution.[146]

The ministry developed a new anthology of Rubén Darío, a Nicaraguan poet and writer, established a Rubén Darío prize for Latin American writers, the Leonel Rugama prize for young Nicaraguan writers, as well as public poetry readings and contests, cultural festivals and concerts.[147] The Sandinista regime tried to keep the revolutionary spirit alive by empowering its citizens artistically.[143] At the time of its inception, the Ministry of Culture needed, according to Cardenal, "to bring a culture to the people who were marginalized from it. We want a culture that is not the culture of an elite, of a group that is considered 'cultivated', but rather of an entire people."[144] Nevertheless, the success of the Ministry of Culture had mixed results and by 1985 criticism arose over artistic freedom in the poetry workshops.[143] The poetry workshops became a matter for criticism and debate.[143] Critics argued that the ministry imposed too many principles and guidelines for young writers in the workshop, such as, asking them to avoid metaphors in their poetry and advising them to write about events in their everyday life.[143] Critical voices came from established poets and writers represented by the Asociacion Sandinista de Trabajadores de la Cultura (ASTC) and from the Ventana both of which were headed by Rosario Murillo.[148] They argued that young writers should be exposed to different poetic styles of writing and resources developed in Nicaragua and elsewhere.[148] Furthermore, they argued that the ministry exhibited a tendency that favored and fostered political and testimonial literature in post-revolutionary Nicaragua.[144]

Economy

[edit]

The new government, formed in 1979 and dominated by the Sandinistas, resulted in a socialist model of economic development. The new leadership was conscious of the social inequities produced during the previous thirty years of unrestricted economic growth and was determined to make the country's workers and peasants, the "economically underprivileged", the prime beneficiaries of the new society. Consequently, in 1980 and 1981, unbridled incentives to private investment gave way to institutions designed to redistribute wealth and income. Private property would continue to be allowed, but all land belonging to the Somozas was confiscated.[149] By 1990 the agrarian reform had affected half of the country's arable land benefiting some 60% of rural families.[150]

However, the ideology of the Sandinistas put the future of the private sector and of private ownership of the means of production in doubt. Although under the new government both public and private ownership were accepted, government spokespersons occasionally referred to a reconstruction phase in the country's development, in which property owners and the professional class would be tapped for their managerial and technical expertise. After reconstruction and recovery, the private sector would give way to expanded public ownership in most areas of the economy. Despite such ideas, which represented the point of view of a faction of the government, the Sandinista government remained officially committed to a mixed economy.[149]

The Sandinista government also significantly expanded workers rights in particular the right to form a union and collective bargaining. Some trade union rights however, like the right to strike were suspended during the Contra War, but strikes still occurred throughout the 1980s, most labour strikes were settled through dialogue with the FSLN.[150]

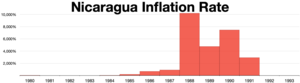

Economic growth was uneven in the 1980s. Restructuring of the economy and the rebuilding immediately following the end of the civil war caused the GDP to rise about 5 percent in 1980 and 1981. Each year from 1984 to 1990, however, showed a drop in the GDP. Reasons for the contraction included the reluctance of foreign banks to offer new loans, the diversion of funds to fight the new insurrection against the government, and, after 1985, the total embargo on trade with the United States, formerly Nicaragua's largest trading partner. After 1985 the government chose to fill the gap between decreasing revenues and mushrooming military expenditures by printing large amounts of paper money. Inflation rose rapidly, peaking in 1988 at more than 14,000 percent annually.[149]

Measures taken by the government to lower inflation were hampered by natural disaster. In early 1988, the administration of Daniel José Ortega Saavedra (Sandinista junta coordinator 1979–85, president 1985–90) established an austerity program to lower inflation. Price controls were tightened, and a new currency was introduced. As a result, by August 1988, inflation had dropped to an annual rate of 240 percent. The following month, however, Hurricane Joan cut a path directly across the center of the country. Damage was extensive, and the government's program of large spending to repair the infrastructure destroyed its anti-inflation measures.[149]

In its eleven years in power, the Sandinista government never overcame most of the economic inequalities that it inherited from the Somoza era. Years of war, policy missteps, natural disasters, and the effects of the United States trade embargo all hindered economic development.[149] Despite these problems however, the Nicaragua economy saw a transformation in a direction to satisfy the needs of Nicaragua's poor majority.[150]

Women in revolutionary Nicaragua

[edit]The women of Nicaragua prior to, during and after the revolution played a prominent role within the nation's society as they have commonly been recognized, throughout history and across all Latin American states, as its backbone. Nicaraguan women were therefore directly affected by all of the positive and negative events that took place during this revolutionary period. The victory of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) in 1979 brought about major changes and gains for women, mainly in legislation, broad educational opportunities, training programs for working women, childcare programs to help women enter the work force and greatly increased participation and leadership positions in a range of political activities.[151] This, in turn, reduced the burdens that the women of Nicaragua were faced with prior to the revolution. During the Sandinista government, women were more active politically. The large majority of members of the neighborhood committees (Comités de Defensa Sandinista) were women. By 1987, 31% of the executive positions in the Sandinista government, 27% of the leadership positions of the FSLN, and 25% of the FSLN's active membership were women.[152]

Supporters of the Sandinistas see their era as characterized by the creation and implementation of successful social programs which were free and made widely available to the entire nation. Some of the more successful programs for women that were implemented by the Sandinistas were in the areas of education (see: Nicaraguan Literacy Campaign), health, and housing. Providing subsidies for basic foodstuffs and the introduction of mass employment were also contributions of the FSLN. The Sandinistas were particularly advantageous for the women of Nicaraguan as they promoted progressive views on gender as early as 1969 claiming that the revolution would "abolish the detestable discrimination that women have suffered with regard to men and establish economic, political and cultural equality between men and women". This was evident as the FSLN began integrating women into their ranks by 1967, unlike other left-wing guerilla groups in the region. This goal was not fully reached because the roots of gender inequality were not explicitly challenged. Women's participation within the public sphere was also substantial, as many took part in the armed struggle as part of the FSLN or as part of counter-revolutionary forces.[153]

Nicaraguan women organized independently in support of the revolution and their cause. Some of those organizations were the Socialist Party (1963), Federación Democrática (which support the FSLN in rural areas), and Luisa Amanda Espinoza Association of Nicaraguan Women (Asociación de Mujeres Nicaragüenses Luisa Amanda Espinosa, AMNLAE). However, since Daniel Ortega, was defeated in the 1990 election by the United Nicaraguan Opposition (UNO) coalition headed by Violeta Chamorro, the situation for women in Nicaragua was seriously altered. In terms of women and the labor market, by the end of 1991 AMNLAE reported that almost 16,000 working women—9,000 agricultural laborers, 3,000 industrial workers, and 3,800 civil servants, including 2,000 in health, 800 in education, and 1,000 in administration—had lost their jobs.[154] The change in government also resulted in the drastic reduction or suspension of all Nicaraguan social programs, which brought back the burdens characteristic of pre-revolutionary Nicaragua. The women were forced to maintain and supplement community social services on their own without economic aid or technical and human resource.[152][155]

Between 2007 and 2018 under Sandinista administrations, Nicaragua has advanced from 62nd to 6th in the world in terms of gender equality, according to the Global Gender Gap Report from the World Economic Forum.

Relationship with the Catholic Church